Building Trust in Law Enforcement through Service Giving Back and Fostering Confidence through Outreach, Education and Prevention Programs

Meet the Experts

Over his 35 years in law enforcement, Zimmerman rose through the ranks, beginning as a rookie patrol officer, then moving up to sargeant and finally ending his career as the lieutenant of police. He has held key positions such as Division Commander of Patrol, Planning, Training and Administration; and SWAT Team Commander. Zimmerman served his career in the police departments of Chicago and Crystal Lake, IL.

Kness retired with 36 years of military service. His assignment as Supervisor of Military Personnel Services (including the Education Benefits Section) provided him with a wealth of knowledge, training and experience working with the GI Bills, scholarships, grants and loans for post-secondary education. His last assignment was the 34th Infantry (Red Bull) Division Command Sergeant Major/E-9.

Test media has been ablaze with stories regarding unfortunate incidents between communities and law enforcement. When this is all the media chooses to focus on, it can paint a falsely negative and many times unfair picture of law enforcement, leading to a misplaced loss of trust by the public. While rebuilding that trust can be hard, it’s not impossible, and police and law agencies across the nation have taken measures to improve their relationships with the communities in which they serve. Through specialized training, community outreach programs and by recognizing the importance of internal affairs and interdepartmental accountability, police departments are once again bolstering the trust and communication within their communities.

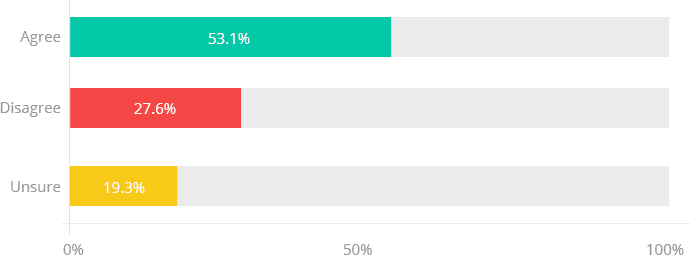

Time Fraime: December 29, 2014 – January 9, 2015

Overall: 3,636 Responses

Forging Connections through Community Outreach

There are a large number of ways law enforcement officers actively give back to their communities. The most successful programs involve the interaction of police with members of the communities. In most cases, that face-to-face interaction is vital to the success of the program. Some of the more successful programs still being used today include:

Launched in 1972 by the National Sheriff’s Association, Neighborhood Watch is one of the oldest and most effective crime prevention programs still in existence. By organizing and bringing together the citizens living in a neighborhood to work together and report suspicious behavior to the police, the opportunities for a potential criminal to commit a crime are greatly reduced.

Many police departments take their K-9 department out to the community and schools to perform demonstrations. As part of the education awareness program, the role and duties of the police officer and dog are explained, as are the techniques used by the handler to help the dog locate victims, suspects, narcotics and bombs.

Many departments offer scholarships specific to the communities in which they serve in honor of a fallen member. The Rodney P. Corbin Memorial Foundation provides one such scholarship. Supported through donations, its mission is to lessen the educational gap in communities by providing scholarships to students and charitable family events through community outreach programs, so that both may overcome challenges and succeed.

The mission of Strategies for Youth (SfY) is to improve police and youth relations through interaction. Through constructive dialogue, each side learns about the other and in the process decreases tension and hostility toward the police. Two tools used as part of the interaction are Juvenile Justice Jeopardy and Think About It First!

Juvenile Justice Jeopardy uses the popular game show format to teach teens how to respectfully interact with the police and to demonstrate the long and short term consequences of their actions.

Think About It First! uses cards to teach youth about the juvenile justice system and consequences of being arrested.

Usually operated at the local level, these programs coordinate with various agencies such as local law enforcement, shelter providers, homeless advocates, community service providers and the legal community to help homeless people find the resources and supplies they need to live day-by-day, with the eventual goal of getting them off of the streets. Homeless Veteran Outreach is a national program operated by the Department of Veteran Affairs which provides homeless veterans the programs and services they need to get a roof over their heads, or prevent them from becoming homeless if they are in danger of losing their homes.

Youth Engagement Programs

Children are one of the most at-risk groups there is when it comes to crimes committed against people. Whether they witness or experience violence, it has a lasting effect on them. If their interaction with the police under these traumatic circumstances is not positive, they run the risk of developing a lifelong distrust of the police. There are numerous programs and training opportunities for children, parents and educators to prevent and curb violence against children. Interaction with law enforcement in these safe environments often serves as a beginning to developing this lasting trust.

The goal of course is for these children to grow up to be productive individuals in their communities and to continue to help foster positive relationships between their communities and law enforcement. Below is a sampling of programs in five different areas that are designed to start the trust development process along with educating youth on specific topics.

Bullying

Bullying in schools is a major problem. Every day up to 160,000 students avoid going to school for fear of being bullied. The Center for Safe Schools uses training, technical assistance, evaluation and research to teach children and educators how to reduce and prevent bullying in their schools.

The newest form of bullying uses the internet and social media to degrade and embarrass teens, some to the point of self-harm or suicide. This cyberbullying program teaches kids how to identify, report and prevent cyberbullying.

An education program designed to understand what bullying is (and isn’t) and to create ways to prevent bullying.

Drug Resistance

Many times children are endangered when their parent(s) or caregiver uses drugs. This one-day class presented by the Midwest Counterdrug Training Center teaches how to recognize drug-endangered children ages infant to five-years-old, the role law enforcement plays as part of a multidisciplinary response team, and successful response strategies that have been used in the past.

An extensive website sponsored by the DEA dedicated to providing information about illicit drugs and their effects. From identification of drugs, to how they are ingested, to their negative effects, to the non-medical consequences of using drugs, this website is a plethora of information avoiding drugs.

A program of the National Sheriff’s Association and The Partnership at Drugfree.org, this program is a substance abuse prevention program aimed at teens 15 to 19 years old that teaches them the consequences and realities of abusing drugs and alcohol.

Law Enforcement & Community Involvement

A big part of police work – commonly overlooked by the media – is community involvement. From educating kids in school about the danger of using illegal drugs through the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program, to providing driver safety education, to coordinating neighborhood watch associations, to speaking at business luncheons, schools and community town hall meetings, police strive hard to make their communities safe and to provide a friendly environment for the people they serve.

D.A.R.E. is one of the first zero-tolerance national programs in the United States. Police officers teaching the D.A.R.E. program undergo 80 hours of instruction, but do not need teaching certificates. They are invited into the schools where they interact with students in a safe and controlled classroom environment. In certain schools, this is the first contact students have with law enforcement in a capacity in which they can see that the police are there to help them. While the focus of the program is avoidance of recreational drug usage and the dangers of joining a gang, the curriculum also teaches assertiveness, making the right decision and the value of self-defense education.

D.A.R.E. training is tailored to the age group being taught. Starting in 4th grade, students are taught how to act in their own best interest when faced with a high-risk situations, such as peer pressure, using inhalants, drinking alcohol and using tobacco. In middle school, the new keep’it REAL curriculum focuses on gangs, internet safety, bullying and over-the-counter drug abuse. Once in high school, the focus changes to recognizing negative feelings and how to cope with them without harming oneself or resorting to using drugs, alcohol or guns.

Building Trust and Legitimacy

Creating a culture of integrity within a department is crucial to building and sustaining community trust, effective policing, and safe communities. A clearly defined standard that guides all actions of every member of a department lays the groundwork for a trusting relationship with the community.

United States Department of Justice

There are several things police departments can do to build trust and legitimacy, beginning with departmental transparency. When the community knows the policies and procedures the police use, and when the police follow those established procedures and hold their officers accountable when the procedures are not followed, the people in the communities begin to again trust the police force hired to protect and serve them.

Next, police have to get out in the community they serve and engage in non-enforcement activities showing they are the guardian of the people and not a warring faction with the people. In diverse communities, the police force should mirror the population as far as cultural and race dispersion. This may entail hiring a more diverse police force that supports the race, gender, language, life experience and cultural background of the people they serve.

Policy and Oversight

Policy and procedure should be spelled out and published to the extent possible on use of force, mass demonstrations, searches, gender and racial profiling and the performance measures used to collect data. The results of the data must also be made available to the public.

Technology and Social Media

Using new technology, especially with the advent of body cameras, builds trust within a community. The departments that have used them report a lower rate of complaints, plus the footage makes it easier to hold the police accountable for their actions should they operate outside of established policies and procedures. Using social media like Facebook is another tool police departments can use to better connect with the community and to increase transparency.

Community Policing and Crime Prevention

When the police work with members of the community to establish how they want to be policed, it not only builds trust within the community – as they have part ownership of the policy and procedures agreed upon – but opens lines of communication. It strengthens the ideal that the police and people of the community should be partners, not opponents.

Officer Training and Education

Societies are changing at a more rapid pace than ever before. The quality and quantity of training the police receives, then, has to change as well, in order to remain relevant. It must address the key issues of today, like crisis intervention, procedural justice, bias and cultural responsiveness, social interaction, and current tactical skills that work best.

Officer Safety and Wellness

Officers should be provided the latest equipment designed to not only keep them alive, but safe, such as the best anti-ballistic vests, and the use of seat belts. Following established policy should be mandated and the consequences stated (accountability) when not used.

Gang Avoidance/Reduction

This gang reduction program is designed to target neighborhoods with known gang activity and reduce their effects through prevention, intervention and suppression, policing and policy.

Gang Resistance And Education Training is an anti-gang and violence prevention program taught in the schools by law enforcement officers. It is built on the premise that early training will immunize youth from joining a gang and prevent delinquent behavior.

Presented by the Law Enforcement Training Academy, University of Missouri, this training teaches law enforcement officers how to handle large gathering of gang members, the handling of gang members during traffic stops, and other motorcycle gang-related trends and topics not only present in Missouri but across the country.

School Safety

A product of the Kentucky Center for School Safety, school administrators, in conjunction with local police, develop programs on how to respond during an active shooter incident. In particular, the focus is target hardening, lock-down drills and hands-on role-playing simulating an active shooter in a school setting.

This program uses federal funding to map out campuses and school administrative facilities using the RESPONSEnet Tactical Mapping System for Schools and Universities software. Mapping increases the safety of students during crisis situations, such as weather emergencies, disasters and school shootings, and enables a faster response from first responders and police. Specifically addressed are the establishment of threat assessment and response protocols.

A product from the National Safe Routes to School program, law enforcement officers assist schools with the development of safe routes to and from schools by accurately assessing potential risks to children that walk or bike to and from school. Issues such as stranger danger, bullying, drug dealing and avoiding crime are addressed and taught to educators, parents and students alike.

A program of the Community Safety Institute, School Safety 101 assists schools in developing a school safety plan tailored to their specific district and schools within that district.

A clearinghouse for information related to ways schools across the nation have used to protect their students from bullying, shootings and gang violence on their campus.

Teen

By using the national sport of baseball, law enforcement officers take off the uniform and become coaches, teaching kids important lessons in teamwork, communication, respect and leadership. The children involved benefit not only from the training on the field, but off of it.

This program helps train local and state law enforcement agencies in the development of policies and procedures to curb the sexual exploitation and proliferation of crimes against children via the internet.

This six-week program is designed to enhance responsible citizenship through the positive interaction with police officers and to educate young people about the challenges and rewards of police work. The program also encourages participants to take part in other NYPD youth programs, such as Explorers, Police Cadet Corps and the Police Athletic League.

A program designed to help detained youth overcome problems they may face once back in their communities, such as gangs, crime and drugs.

The Teen And Police Service Academy is a training program of the Houston Police Department that trains police officers how to build trust with at-risk youth. Sample topics in this 15-week curriculum include issues, causes and prevention of violence, physical and sexual abuse, stalking and bullying, to name a few.

Funding for this program assists with the development and implementation of programs designed to hold delinquent tribal youth accountable for their actions and to strengthen tribal juvenile systems in Native American sovereign nations.

Community & Police Improvement Initiatives

When the police and the communities they serve work together, good things can happen. Two organizations that work hard to build trust and make communities safer places to work and live are COPS and the IACP. Both have several initiatives they are committed to, but for different purposes and outcomes. While the COPS program is more aimed at educating communities, the IACP programs focus on training law enforcement officers and department professionalism and how to better interact with the communities they serve. The work done by both organizations improve relationships between the police and people, and serve to build trust thus making communities safer places to live and work.

The Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Program’s mission is to advance public safety through initiatives designed to build trust and mutual respect between law enforcement and the communities they serve. As an extension of the U.S. Department of Justice, COPS provides resources that help bring the police and communities together to improve relationships with minority populations, prevent crime and provide fairer enforcement. Some of their successful initiatives include:

- Because Things Happen Every Day

- Smart on Crime

- Value-Based

- Safe Schools

- Anti-Gang

Anti-Gang Initiative

COPS provides grant money for communities to advance their public safety through enforcement, prevention, education and intervention of gang activity, led by task forces comprised of local, state, federal and tribal law enforcement agencies (if applicable). By reducing gang activity, communities are safer and teens are less likely to get involved in a path that eventually leads them to committing major crimes resulting in prison time.

Because Things Happen Every Day

STAR (Students Terminating Abusive Relationships) speaks out against violence, both interpersonal and societal, in an effort to promote relationships based on equality, respect and trust. Community organizations working with the police include schools, Boys and Girls Clubs, YMCA/YWCA, Students Against Drunk Driving (SADD) and other organizations that serve the adolescent population.

Safe Place operates a hotline and provides free, confidential counseling to teens and works closely with school counselors and staff to form support groups for teens staffed by teens.

STAR (Students Terminating Abusive Relationships) speaks out against violence, both interpersonal and societal, in an effort to promote relationships based on equality, respect and trust. Community organizations working with the police include schools, Boys and Girls Clubs, YMCA/YWCA, Students Against Drunk Driving (SADD) and other organizations that serve the adolescent population.

Safe Schools Initiative

When students succeed, the whole community succeeds. Part of the Safe Schools Initiative is the School Resource Officer Program. It forms a problem-solving partnership with law enforcement, school administrators, parents and students on how to make schools safer. The philosophy behind the SRO program is that students make more positive contributions and achieve more when in a safe environment. That success carries over into the community and they become more productive citizens in their communities. A side benefit is that students get to positively interact with a police assigned to their schools in a safe and non-threatening environment.

Smart on Crime Initiative

With limited resources, this COPS program looks at how to better use prison funding by still incarcerating violent crime offenders, but reducing sentences of non-violent offenders. Through this program, New York and New Jersey were able to reduce their prison populations by 26 percent and 24 percent respectively, while dropping crime by 31 percent and 30 percent respectively, during the same period in time. Fairer enforcement builds trust in the communities and in many cases keeps the breadwinner out of prison, which better serves the family as well.

Value-Based Initiative

Designed to strengthen communities through partnerships between police and faith-based organizations, VBI provides resources to help faith congregations improve the quality of life through community outreach programs. The police know that the best way to deter crime is to get to the root of the issues in the community causing the crime.

Because faith-based organizations are deeply rooted within a community, they many times have a better insight into the real issues that need to be addressed to affect crime. By partnering with the police, resources can then be funneled to the areas that need them the most.

The IACP’s mission is to advance the professionalism of police forces. A well-trained force exhibits better ethics, integrity and professional conduct, which reflects a better interaction and trust between communities and their police. While the IACP has 42 initiatives in total, five of the more popular ones that effect communities the most include:

- Safeguarding Children of Arrested Parents

- Violence Against Women

- Gun Violence Reduction

- Project Safe Neighborhoods

- Countering Violent Extremism

Countering Violent Extremism

Aimed at recognizing and countering extremist activity, this training teaches law enforcement officials how to use the internet and social media to search out and recognize the promotion of radicalization for violence. The training also teaches police forces and communities on successful problem-solving techniques used to counter extremists’ activity on social media sites.

Gun Violence Reduction

The use of firearms in violent crimes is a topic of great concern within the police community. This initiative addresses gun violence by training police forces how to better interdict the trafficking of firearms and disrupt the criminal activity associated with the use of guns, including domestic abuse, carjacking, robbery, assault and murder. Some police departments have been very successful at getting guns off the street by using a gun buy-back program.

Project Safe Neighborhoods

Mainly aimed at gang reduction, this training improves the knowledge, communication and collaboration between police forces and communities in an effort to reduce, disrupt and eradicate gangs and the associated crime they cause in communities. Targeted in particular is training on gang recognition, including the specific clothing, colors, graffiti and other signs gangs use to denote their presence and territory.

Safeguarding Children of Arrested Parents

When the police come knocking at the door of a home to arrest a parent, it can have a traumatic effect on the children. In 2010, one in 28 children experienced this event. Shock, fear, anxiety or anger at the arresting officers are just some of the emotions children can exhibit, with the negative effects lasting for weeks, months or even years. As children mature, the experience they had can carry over and is counter-productive to building trust between their communities and law enforcement agencies.

Under this initiative, however, police departments receive training on how to establish and implement an effective children safeguarding policy where officers consider the emotional and physical well-being of the children during a parent arrest. Keeping the well-being of the children at the forefront during a parent arrest has shown to have a lasting positive effect.

Violence Against Women

Under VAW, law enforcement executives are trained how to better employ their resources to respond to, investigate, intervene, prevent and eliminate violence against women. Whether in the home, on campus, in the workplace or on the streets, women are victims of domestic violence, stalking, sexual assault and human trafficking. VAW helps officers learn the best ways to help and serve these women.

The greatest indication of success with any outreach initiative involvin community policing is when you see residents, who otherwise would not turn to officers for help, reach [out] and get involved.

Hopkins police departmentPrograms in Action: Success Stories

How Communities Can Support Law Enforcement

Cops are not the only ones who need to take responsibility for building and maintaining a positive relationship with the people they serve. Communities should also be taking active steps to ensure that trust is being built, and engaging with the police force in positive ways. How can communities do this? These five steps can being the process of creating a solid foundation for community and law enforcement engagement:

It starts with the willingness of community leaders to want to forge that relationship. Due to recent events (Ferguson, MO and Baltimore, MD are two that come to mind), the tension between police and some communities went up and consequently eroded the trust that previously did exist. In these cases, the trust process will have to start at the bottom once again and slowly build from there; it will not be a quick or easy process to get back to where is was, let alone to advance beyond their high-point.

Community leaders have to teach their people that the police are there to protect their civil rights and civil liberties; to enforce the fact that the police are not the bad guys, but at times, they must do what can be perceived as detrimental to the community in the performance of their jobs – especially when community members are breaking the law. Offenders have to be arrested in order to protect those not involved. However, the method in which the police carry out the law can either enhance the trust process or degrade it, so it is a two-way street. Trust on both sides is not given, it has to be earned.

If members of the community see suspicious activity, it is their duty to report it to the police. A public awareness campaign coined “If you see something, say something” is intended to do just that: the police (and ultimately the community) by reporting suspicious activity. Having members of the community respond can nip criminal activity in the bud before it has had a chance to negatively impact everyone.

Communities must encourage day-to-day interaction with police on the street. Dialogues under friendly conditions go a long way toward building trust on both sides. The police will be out patrolling anyway; it is up to the members of the community to make the contact positive.

Lastly, communities must invite local, state and federal law enforcement officials to take part in their community meetings. Not only will attendees from the community get to know their law enforcement, but law enforcement will get to know the specific issues within the community that they may be able to help solve.

One community that successfully restored trust with their police department is Boise, ID. In 2000, when the Office of Community Osbudsman was created, there were 76 complaints against its police officers that year. Over the next 14 years, the number of annual complaints dropped, eventually reaching an all-time low of six in 2014. How did they do it?

By working with their police department to become more transparent. When the police policies and procedures are made public to the community, and the people see the police are following their own operation practices, it builds trust between the two entities. The office has requested their name be changed to the Office of Police Oversight as they think it better reflects their mission in their community.

However, for many police departments and communities, an attempt to bridge this gap is termed community-based policing. Both sides view it as a program that can be implemented to fix trust problems when in fact it is not that at all. It is an arduous process that is continually evolving over time requiring the full participation of both sides. The Police Department in Lincoln, NE started its community-based policing back in 1975. Long after Los Angles and Cincinnati cast similar programs aside, Lincoln is still at it and has been tweaking their initiative ever since. Lincoln’s Public Safety Director Tom Casady said it best in a paper on Lincoln’s community-based policing:

You can’t tell whether community policing exists in a city on the basis of the press release, the organizational chart, or the annual report. Rather, it can best be discerned by observing the daily work of officers. It exists when officers spend a significant amount of their available time out of their patrol cars; when officers are common sight in businesses, schools, PTA meetings, recreation centers; when most want to work the street by choice; when individual officers are often involved in community affairs-cultural events, school events, meetings of service clubs, etc., often as an expected part of their job duties.

It exists when most citizens know a few officers by name; when officers know scores of citizens in their area of assignment, and have an intimate knowledge of their area. You can see it plainly when most officers are relaxed and warmly human – not robotic. When any discussion of a significant community issue involves the police; and when few organizations would not think of tackling a significant issue of community concern without involving the police. The community-based police department is open – it has a well-used process for addressing citizen grievances, relates well with the news media and cultivates positive relationships with elected officials.

Ethics & Integrity Education for Law Enforcement

Even with importance of ethics and integrity well documented, department still must vie for limited training time and funds. However, knowing the ethical thing to do in a certain situation – and having the integrity to do it – are the very foundation that makes all other training succeed. Recent high profile events are starting to put the focus back on ethics and integrity.

Teaching ethical decision-making in general is not easy; each decision involves options, making choices, and living with the consequences. For the police professional, it is even more difficult: making an ethical decision requires considering the various options, selecting one of the options, implementing it, and then knowingly being held accountable for the outcome – all within a split-second. Any given officer may have to make several of these split-second decisions during the course of a shift. Because of the high levels of accountability maintained, making the wrong choice can be career-limiting, to say the least.

Sample Courses

Many departments offer ethics and integrity training as part of their continuing education/refresher education requirement. Some of these courses include:

Cultural Competency 101 Training Package for Law Enforcement Personnel: a department-wide training program that brings awareness to race, cultural and class issues that exist within a community and how to increase relations within the community. The class addresses four key aspects of this issue:

- Race, culture and class background

- Rapidly changing demographics

- Community history and politics

- The culture of law enforcement work itself

Domestic Violence & Law Enforcement Ethics: this two-part course serves as refresher training for individual officers. The first part, Domestic Violence, emphasizes changes in law through case and statutory review along with practical discussions concerning enforcement of orders, Emergency Orders of Protection, warrant-less arrests, Double Jeopardy, etc. Assessment consists of case-briefings and application to real situations. The second part, Law Enforcement Ethics, is designed to enhance the ethical decision-making process by discussing some of the common issues dealt with which are unique to the law enforcement field.

Ethical Leadership: in a class environment, it uses exercises to discover one’s ethics and how to effectively apply them on the job. This course provides participants with a pragmatic understanding, reflection and continued discussion of ethical issues and dilemmas in life and the workplace. Participants will engage in exercises to further determine their own ethics and how to effectively apply them within their organization.

Police Morale for Supervisors – It Is Your Problem: serves as either as initial training for new supervisors or refresher training for the experienced. Poor employee morale is a serious problem facing law enforcement and one that, if not confronted and corrected, will threaten the mission, productivity, discipline, and even the integrity of a police agency. With stakes so high, it is only natural law enforcement managers make raising employee morale a top priority.

Professionalism and Ethics: for the individual officer, the course reviews rules of conduct and ethical decision-making. Understanding that professionalism and ethical behavior ultimately ensures safety and consistency in the workplace, officers will be educated on the expectations of the department/agency and the choices they make which will have an everlasting impact on their career as a law enforcement/correctional professional.

Ethics is our greatest training and leadership need today and into the next century. In addition to the fact that most departments do not conduct ethics training, nothing is more devastating to individual departments and our entire profession than uncovered scandals or discovered acts of officer misconduct and unethical behavior.

International Association of Police ChiefsOpportunities for Continuing Law Enforcement Education

To help build – and maintain – the skills required for police officers to function effectively within their community, and to keep abreast of how their community is evolving, they have to undergo periodic refresher training. Some of the following opportunities are free, while others have a charge associated with them. The venues are varied between live seminars, downloadable presentations, and online/on-campus classroom offerings.

Crisis Communications: Offered by the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement, this free training teaches emergency telecommunicators how to be more proficient in stressful situations. Ideal training for 911 operators, dispatchers and officers in the field.

Cultural Diversity: Legislatively-mandated training in the state of Texas, this Powerpoint/Word training presentation increases the awareness of the influence of our cultural rules, values, beliefs and prejudices have on the way we act in a situation. The training promotes mutual respect and enhances the awareness of an understanding of human diversity issues through providing skills to enable to effectively interact with persons of diverse populations.

Dispatcher Ethics: A video series that explores what you believe to be ethically right and how knowing yourself will help you make the right decisions when faced with a law enforcement situation.

Hate Crime Courses for CA Agencies: This one-day POST-certified course is designed for law enforcement officers who are first responders to a hate crime or hate incident. It provides up-to-date information to assist officers in the safe and successful handling of bias-motivated crimes.

Improving Ethics Training for the 21st Century: An article posted on policeone.com emphasizing the need for ethics in any organization, but especially law enforcement.

Law Enforcement Ethics: This online training course helps officers by explaining the dynamics of ethics in the law enforcement field, how to better understand the ethical dilemmas of fellow officers, and how to avoid ethical pitfalls.

Leadership through Understanding Human Behavior: As an exportable, this class provides law enforcement leaders with a training vehicle that can help them develop more effective workgroups and teams. Participants will develop a better understanding of themselves, interpersonal dynamics, and how their strengths, weaknesses, and roles within workgroups and teams affect a mission’s outcome.

Less Lethal Techniques: In particular, this online course explores several aspects of potentially dangerous response calls, including excited delirium and positional asphyxia, and the less lethal, more appropriate restraint techniques that might be applied in these situations.

Mental and Elderly Response: This online course from the OSS Academy it explores how mentally ill and elderly response calls can be tedious and potentially dangerous. Many factors have to be taken into consideration when approaching these individuals. This course details the verbal, environmental and behavioral cues that should be considered when responding to calls for service.

National Coalition Academy: Consisting of classroom, distance learning and online classes, students develop skills in 15 key areas for community problem solving, such as assessing community needs, enhancing cultural competence, and creating and maintaining community coalitions and partnerships.

People In Crisis: A video training program on how to recognize and de-escalate crisis situations.

Principles for Promoting Police Integrity: A 45-page downloadable PDF from the Department of Justice of examples of police practices and policies that enhance the integrity of officers and departments as a whole.

Racial Profiling: An online course that provides the necessary training to bring awareness and understanding about how and why racial profiling occurs, and why it is necessary to eliminate it in your community.

Social Media Certification: From LAwS Academy, this course gives police officers the tools needed to leverage social media resources. In today’s connected world, social media is a critical component to a successful law enforcement strategy. From developing sophisticated methods for investigation, crime solving and prevention, to improving communications with citizens and enhancing transparency, agencies that effectively use social media tools are more efficient, effective and more trusted within a community.

Street Crimes: A live seminar hosted by the St. Louis County & Municipal Police Academy that provides up-to-date street-tested information on how to stay one-step ahead of criminals, thus making a community safer by preventing crimes before they happen.

Interview

with an Officer LT (Ret.) Anthony Zimmerman,Sr. on Rebuilding Police-Community Trust

Lt. Zimmerman has been heavily involved in police training throughout his career, serving 23 years as adjunct professor at Harper College in Palatine, IL. He has also taught law enforcement classes spanning 39 years as Instructor of In-Service Police Training at Crescent Regional Training and Northeast Multi-Regional Police Training Center, both in Illinois.

What is causing the mistrust of police officers and the current backlash departments are facing, such as we saw at Ferguson, MO?

In my opinion and experience from my 35 years in law enforcement, there has always has been mistrust of police in the lower income, higher crime areas of a city by the younger folks. In part, it is because their age group accounts for the largest number of arrests made against their fellow citizens in their community.

Another factor is the rise of social media. It has had a field day against officers who are trying to maintain order. A good example is ISIS who is using it in a campaign to motivate their lone wolves lurking in this country or others who are looking to be part of something greater, so they try their hand at 15 minutes of fame by hunting down police officers.

And then there is the media itself. They tend to inflate the animosity towards law enforcement with their sensationalized slant on publishing.

The community cries about a lack of transparency of the police department, but they do not understand if an incident is under investigation, the details cannot be shared or released until the investigation is complete.

Of course some of our Federal, State and local politicians have seem to take an anti-police stance lately too. That does nothing but inflame the animosity of the people against its police. It is easy to blame the officers involved prior to knowing all the facts surrounding an incident.

In today’s world, it seems to me as though the police officer has become the hunted. In my career of policing, I never have seen it this bad.

What are police departments currently doing that is working as far as building the trust of the people?

Town hall and community meetings work – when you can get the people to attend. And the people have to be willing to change their community for the better. The problem is in many of these communities with high crime, the gangs and criminals have such tight control that people don’t want to come to meetings in fear of retribution. In communities that have changed, once the conditions get too caustic for the gangs and criminals to easily operate (and make money), they move elsewhere where they can operate more freely. So change can happen if the community is willing to work with the police to make it happen.

What are some community outreach, ethics and integrity programs or training that you know are making a difference within a community?

Programs that work in the various cities that have low crime rates are those that involve a high interaction between citizens and the police. A few programs that I personally have experience with that come to mind are Crime Stoppers, Citizen Police Academy, Neighborhood Crime Watch and Police Ride-Along programs. We have seen real success with these programs in some communities. We need the eyes and ears of the people in the community to help us “take a bite out of crime.” However in high crime areas, these programs do not work as well for the exact reasons stated in the previous question.

What are some continuing education options for law enforcement that improves the trust between a police officer and the community they serve?

Police are in constant in-service training on various subjects from ethics, to integrity, to community involvement and more. But if the community is unresponsive and doesn’t meet the police half-way, there isn’t much the police can do to make the situation better regardless of the amount of training received, except to keep trying to build trust with the people they serve. The community has to be willing to help and want change too in order for it to work.

One of the best tools and training to come along lately are the use of body cameras. Because arrests and altercations are now filmed, it keeps both the citizens and police accountable to each other. In departments where they have been used, complaints from citizens are down across the board.

The Importance of Internal Affairs

When trust between a police department and its community exists, it is usually due to the work done by a police department’s internal affairs department. Whether a department has a separate internal affairs section, an officer assigned the additional duty or uses a third-party, when the people can see the police holding themselves accountable for misconduct, corruption, inappropriate behavior or not adhering to policy and procedure, it builds trust that the department, as a whole, is looking out for their best interest.

Internal affairs can also protect its own officers from false or malicious accusations from people in the community. By using a standardized complaint process, it can clear its officers of wrongdoing or confirm accusations from the people and hold officers accountable. When the community see the same process used across the board, it develops or maintains trust in the community. If separate processes were used, the double-standard would erode trust.

In the past, a commonly used model of building community trust looked like this:

-

Safe Community

-

Recruiting and Hiring

-

Ethics Training and Education

-

Early Intervention System / Risk Management

-

Effective Policing

-

Community Trust, Response, and Support

-

Internal Affairs

-

Building Capacity and Sustainability

However, as a result of President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, the recommended model has changed. The Final Report found these six pillars are the foundation of establishing trust today between police departments and communities:

An Experiment of Police Culture Change

In 2009 the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) completed a reform of their department that had begun in 2000. During the 90s, the LAPD had a variety of police crises beginning with the 1991 beating of Rodney King and ending with the 1999 Rampart police corruption scandal within the department. Under the threat of a lawsuit by the Department of Justice for a “pattern-and-practice of misconduct,” the city agreed to a consent decree where the department would transform, under the supervision of the Federal court. The reform would include adopting scores of improvement measures drafted by the Justice Department.

The Transformation

But was the transformation successful? To answer this question, the Harvard Kennedy School examined the LAPD by using a series of research methods including:

Observing the department from the patrol officer on the street to the highest echelons of command.

Analyzing crime, arrests, stops, civilian complaints, police personnel and use of force data.

Compiling 10 years’ worth of surveys of police officers and residents of Los Angeles.

Conducting three surveys of their own: one of residents; one of LAPD officers; and one of detainees recently arrested by the LAPD.

Conducting a series of focus groups and interviews with police officers, public officials and residents of Los Angeles.

The results illustrate how police/community relations can improve when provided the proper catalyst. They found the LAPD had changed considerably from what it was when the decree was first implemented in 2000; the most change happened in the last five years of the decree, indicating that it took four years to see a significant change in a decade-old culture of misconduct within the police department.

The Results

In a snapshot, what the Harvard Kennedy School found was:

Public satisfaction had increased; 83 percent of LA residents said their LAPD is now doing a “good” or “excellent” job.

The use of serious force fell each year since 2004, despite the views of some officers that the decree inhibited them from doing their job.

Both the quantity and quality of enforcement activity increased substantially; the quantity of pedestrian and motor vehicle stops doubled since 2002; the quality of stops increased due to a higher proportion of those stops resulting in felony charges.

In 2009, the LAPD was taken off of the decree. Under their reformed culture, they have maintained their good standing within the community, indicating permanent change and showing that a repair of police/community relations can happen within a police department and the community it serves.